The New York Times has offered this calendar to readers since 2017. It’s a collection of newsworthy events in spaceflight and astronomy curated by the paper’s journalists.

The entries below these instructions will be updated regularly to adjust dates and revise information. New events will be added and entries will be removed after they conclude or are indefinitely postponed.

The easiest way to use this calendar is to add this page to your web browser’s bookmarks or favorites, and revisit it regularly. Instructions for common web browsers are below, along with additional instructions and answers to common questions.

Answers to common questions we’ve received

How do I bookmark this calendar on my browser?

Here are bookmarking instructions for four of the most common browsers:

What happened to the Google Calendar, Apple Calendar and Outlook calendar feeds?

The Times has paused the use of the feed that puts the events from this calendar on your personal digital calendar.

If we resume use of such a feed, we will post instructions for it at this page.

How do I unsubscribe from the digital calendar feed?

You can follow the instructions included in last year’s edition of the calendar.

Our species called this latest 366-day journey around the sun “2024” and packed into it a ton of astronomical and spaceflight excitement.

A solar eclipse crossed North America. Two robotic landers reached the lunar surface, largely intact. The most powerful rocket booster ever built was caught by a pair of mechanical arms nicknamed “chopsticks.” A journey began to Jupiter’s icy ocean moon Europa. And private astronauts conducted a daring spacewalk.

Can this revolution around the sun we name “2025” compare? We’ll let you be the judge of how enthusiastic to get about the events you can expect on the launchpads and in the night sky.

For updates on these and other events, you can make regular visits to The Times Space and Astronomy calendar.

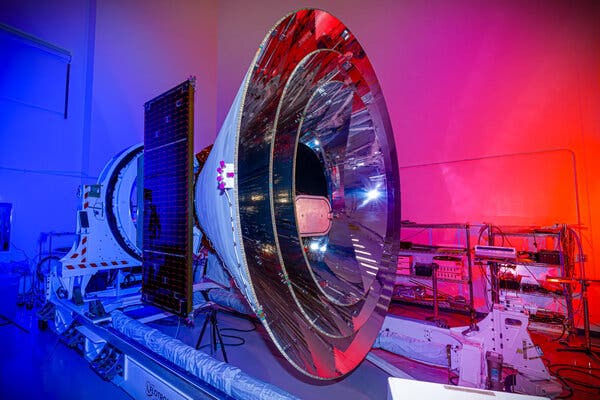

Jeff Bezos enters the arena

Through SpaceX, Elon Musk has dominated spaceflight around the planet in recent years. But the extraplanetary ambitions of the Amazon founder Jeff Bezos could present a challenge to Mr. Musk soon.

The space company started by Mr. Bezos, Blue Origin, has a powerful rocket called New Glenn that may at last get off the ground in 2025. Like SpaceX’s Falcon 9, the booster stage is designed to be fully reusable so it can fly again and again and reduce the cost of launches. The rocket could launch national security satellites for the U.S. military and spacecraft for NASA, including orbiters to Mars and moon landers.

Another thing New Glenn will carry is satellites for Amazon, where Mr. Bezos is still executive chair. The company’s Project Kuiper involves plans to build a mega-constellation of satellites beaming internet down from space, in competition with SpaceX’s Starlink constellation. Amazon also plans to launch Kuiper satellites using rockets from many of Blue Origin’s competitors, including United Launch Alliance, Arianespace of France and even SpaceX.

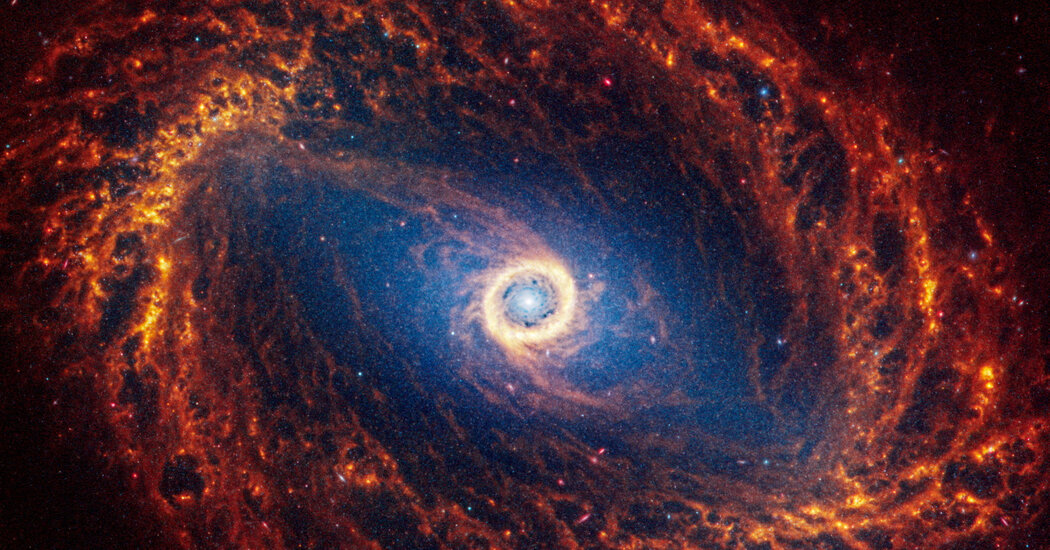

Rubin’s first light

Astronomers atop a mountain in central Chile are wrapping up construction of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which might capture its first views of the night sky this year, as early as July 4.

Formerly the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, the observatory was renamed in 2020 to honor Vera Rubin, who died at 88 in 2016. Dr. Rubin’s work persuaded astronomers of the existence of dark matter, which makes up a vast majority of mass in the universe, but no one knows what it is.

The name is fitting. With the largest digital camera in the world, scientists will use the Rubin Observatory to create a time-lapse motion picture of the Southern sky. Such images would help researchers understand the nature of dark matter, as well as dark energy, the unknown force pushing the cosmos apart. The trove of data will also help reveal the story of our galaxy’s birth and catalog asteroids and comets in our solar system, including those that could slam into Earth one day.

The moon, and Trump, come back around

During the first administration of Donald J. Trump, American space policy refocused on lunar exploration. President Biden’s administration sustained that direction. But as Mr. Trump returns to the White House in January, the country’s existing space plans could be upended by canceling the expensive rocket NASA has been developing for more than a decade. Alternatively, Mr. Trump could more radically shift NASA’s focus to sending people to Mars. Getting to the Red Planet is the primary goal of Mr. Musk, who has been advising the president-elect.

For all that potential uncertainty, a series of robotic space missions are planned to the moon early in the year. The first two, a pair of landers from the American company Firefly Aerospace and the Japanese company Ispace, will launch on the same SpaceX rocket as soon as mid-January. The mission by Firefly will be the first trip of its Blue Ghost lander and will carry cargo paid for by NASA. The lunar trip by Ispace will be its second attempt after the company’s first lander crashed into the moon’s surface in 2023.

Later in the year’s first quarter, Intuitive Machines may try to put another robotic lander on the moon after the company’s Odysseus lander reached the surface intact, but tilted over, last February. The company’s second lander, named Athena, also will carry NASA-financed instruments, including a drill that will try to find samples of ice. Athena will share a SpaceX launcher with Lunar Trailblazer, a NASA orbiter that will study water on the moon.

Vigils for Voyagers 1 and 2

Voyagers 1 and 2, twin spacecraft that inspired a generation of cosmic wonderers, were launched in 1977. After decades of exploring the outer solar system before charting the unknown frontier of interstellar space, the two spacecraft are showing signs of age.

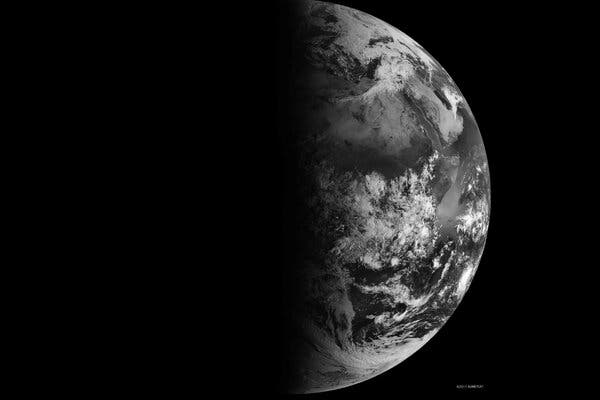

Early in their journey, the pair swooped past Jupiter and Saturn, and Voyager 2 later visited Uranus and Neptune. But perhaps the mission’s most iconic gift to the world was a photo taken of Earth, a tiny pixel against the expanse of space, leading the famed astronomer Carl Sagan to coin the image “Pale Blue Dot.”

In recent years, the robotic explorers have each blinked in and out of contact with NASA. Communication with Voyager 2 was purposefully shut down in 2020 for months, then lost by accident for a couple of weeks in 2023 before it was restored.

Voyager 1, on the other hand, gave mission specialists a scare this year when it stopped sending data back to Earth. Instruments on both spacecraft have been shut down to conserve power.

But NASA isn’t giving up on them yet. When they are eventually interred in the space between the stars, it would be an apt resting place given how the duo has ventured where no other spacecraft had gone before.

India’s orbital objective

India’s space program has landed a robot on the moon and put a spacecraft into orbit around Mars. The country’s most immediate priorities are much closer to Earth, but that doesn’t mean they are less ambitious.

India is focusing on human spaceflight. A member of the nation’s astronaut corps, Shubhanshu Shukla, is to spend up to 14 days this spring aboard the International Space Station during a commercial mission with the company Axiom Space.

Mr. Shukla and his fellow Indian astronauts are hoping to be the first to launch to low Earth orbit on its homegrown rockets. India said in December that an orbital vehicle from that program, known as Gaganyaan, was being prepared for a test launch with no astronauts aboard. A successful flight could lead the way to a crewed Indian astronaut launch as early as 2026.

New milestones and new spacecraft

SpaceX wowed the world in November during Flight 5 of Starship, the most powerful rocket ever built. Expect the company to try to repeat the stunning “chopsticks” catch of its massive Super Heavy booster. SpaceX may also attempt to catch the upper-stage Starship vehicle after it completes an orbit of Earth and returns to the launch site in South Texas for the first time. SpaceX said it was aiming for 25 launches of Starship in 2025 as it prepares the spacecraft to land astronauts on the moon under the company’s contract with NASA.

Other new rockets and spacecraft may take flight in 2025.

One is Neutron, a reusable rocket being developed by Rocket Lab, which was founded in New Zealand. The company routinely carries satellites to orbit aboard its small Electron rocket, and could conduct a first flight of the new vehicle from a launch site in Virginia.

Another is Dream Chaser, a space plane built by Sierra Space. After delays in 2024, the company hopes it will carry cargo to the I.S.S. for the first time this year.

Active from Dec. 26, 2024, to Jan. 16. Peak night: Jan. 2 to 3.

The Quadrantids, which the International Meteor Organization says could be one of the strongest meteor showers this year, are also one of the few caused by debris from an asteroid. Best viewed from the Northern Hemisphere, the shower is one of the toughest to catch.

The Quadrantids have one of the shortest peak periods, lasting only six hours. And the time of year might mean cloudy skies and frigid temperatures. The moon will be about 11 percent full, which may also make meteors harder to spot.

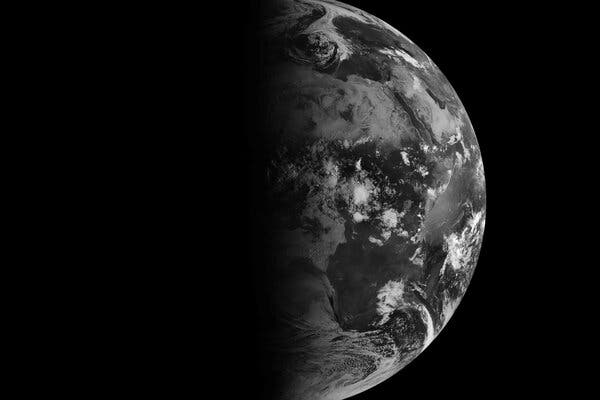

Even as the Northern Hemisphere experiences winter’s chill, our planet on Saturday will be at perihelion, the closest it gets to the sun during its elliptical orbit. Learn more about planetary orbits and the search for life around the galaxy.

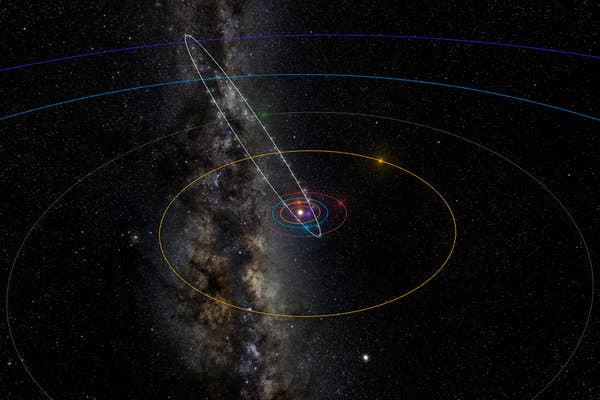

Discovered last year, Comet ATLAS, known as C/2024 G3 to astronomers, may burn brightly enough to be seen without a telescope when it reaches perihelion, the closest it will get to the sun.

Many comets burn up when they get too close to the sun’s heat. If this one survives the solar encounter, it could be the most vibrant comet visible from Earth all year. But the full moon this night might make it more difficult to spot.

As the full moon travels through the sky this evening, it will pass in front of Mars for stargazers in Africa and the Americas.

The event, known as a lunar occultation, occurs as the Red Planet appears bigger and brighter than usual. That’s because two days later, Earth will be oriented directly between Mars and the sun, the closest the pair will get for two years, in an event known as opposition.

A pair of landers, from the American company Firefly Aerospace and the Japanese company Ispace, will head to the moon using the same SpaceX rocket.

The Firefly mission, which is carrying cargo paid for by NASA, will be the first trip of its Blue Ghost lander. The lunar trip by Ispace will be the company’s second attempt after its first lander crashed into the moon’s surface in 2023.

We will provide a more precise launch date for this mission when SpaceX announces it.

The company Intuitive Machines put its robotic Odysseus lander on the moon’s surface intact, but tilted over, last February. It was the first American vehicle to make a soft landing on the moon in more than 50 years.

Its second lunar lander, named Athena, will head there carrying NASA-financed instruments including a drill that will try to find samples of ice. Athena will share a SpaceX launcher with Lunar Trailblazer, a NASA orbiter that will study water on the moon.

We will provide a more precise launch date for this mission when SpaceX announces it.

If astronomers could study space in more colors, they’d gain a better understanding of cosmic physics and planetary science. That’s the goal of NASA’s SPHEREx mission, imaging the sky in 102 colors, many of which are infrared and aren’t visible to humans. SPHEREx stands for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer. We will provide a more precise launch date for this mission when NASA and SpaceX announce one.

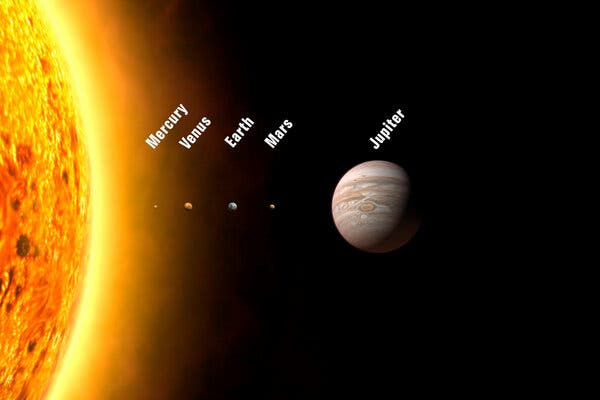

Some stargazers are calling it a planetary parade: Every other planet in our solar system can be seen in the sky tonight. Mercury, Venus, Mars and Jupiter will be visible with the unaided eye. Saturn, Uranus and Neptune will be up there, too, but require binoculars or a telescope to find.

Earth’s shadow will cross over the moon, creating the effect that some call a blood moon. The eclipse will be most visible across parts of the Americas and the Pacific, but also experienced in Europe and western Africa.

The vernal equinox is one of two points in Earth’s orbit where the sun creates equal periods of daytime and nighttime across the globe. Many people mark it as the first day of the spring. See what it looks like from space.

If you saved your eclipse glasses from last April’s Great North American Eclipse, you might get a chance to use them again for this partial solar eclipse. But you’ll have to wake up early and hope for clear skies not long after sunrise for this one. Do not look directly at a partial eclipse.

Along many parts of the East Coast, the eclipse’s effect will be modest. There will be only about a 20 percent bite out of the sun in New York City. You’ll have to venture high into Canada’s Maritime Provinces to find a place where the sun nears a total eclipse.

The NASA-ISRO SAR mission, or NISAR, is a collaborative project between the American and Indian space agencies. Launching from an Indian rocket, the spacecraft will carry a variety of sensors, some provided by NASA, to study shifts in Earth’s land- and ice-covered surfaces using synthetic aperture radar.

NASA says the launch will most likely occur in March. The flight was delayed last year after additional work on its instruments. We will provide a more precise launch date for this mission when NASA and India’s space agency, ISRO, announce one.

Visits to the International Space Station are valuable, and would-be astronauts and their countries can wait a long time for the opportunity. Now an American company, Axiom Space, is organizing trips there for wealthy adventurers and for people from countries that have seldom or never had astronauts aboard the orbital outpost.

Most notable among the crew of the company’s Ax-4 flight is the Indian astronaut Shubhanshu Shukla, who has been tapped to fly to orbit on his country’s first crewed spaceflight mission, called Gaganyaan. He will share a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule with Slawosz Uznanski of Poland and Tibor Kapu of Hungary.

Active from April 15 to April 30. Peak night: April 21 to 22.

Best seen from the Northern Hemisphere, the Lyrids are caused by the dusty debris from a comet named Thatcher and spring from the constellation Lyra.

During this year’s period of peak activity, viewers may have a more difficult time seeing meteors from this shower because the moon will be 40 percent full.

Active from April 20 to May 21. Peak night: May 3 to 4.

The Eta Aquarid meteor shower is known for its fast fireballs, which occur as Earth passes through the rubble left by Halley’s comet.

Sometimes spelled Eta Aquariid, this shower is most easily seen from the southern tropics. But a lower rate of meteors will also be visible in the Northern Hemisphere close to sunrise. The moon will be nearly half full on the night of the show.

It’s the scientific start to summer in the Northern Hemisphere, when this half of the world tilts toward the sun. Read more about the solstice and why it happens.

Even as the Northern Hemisphere experiences the heat of summer, our planet is at aphelion, the farthest it will get from the sun during its elliptical orbit. Read more about aphelion, why it happens and why it’s decreasing.

In Chile, an American-funded telescope is coming into operation that will use the largest digital camera in the world.

Scientists will use the Rubin Observatory to create a motion picture of the southern sky, helping them understand the nature of dark matter, the invisible glue holding our universe together, as well as dark energy, the unknown force pulling the cosmos apart. That trove of data will also reveal the story of our galaxy’s birth and become a catalog of asteroids and comets in our solar system that could one day be hazardous to Earth.

Originally named the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, the observatory was renamed in 2020 to honor Vera C. Rubin, whose work convinced astronomers of the existence of dark matter. Dr. Rubin died in 2016 at 88.

Southern Delta Aquarids active from July 18 to Aug. 12.

Alpha Capricornids active from July 12 to Aug. 12.

Peak night for both: July 29 to 30.

Two meteor showers peak at the end of July: the Southern Delta Aquarids, best seen in the Southern Hemisphere in the constellation Aquarius, and the Alpha Capricornids, which are visible from both hemispheres in Capricorn.

With the moon around 27 percent full, viewing opportunities could be favorable. But the Southern Delta Aquarids, sometimes spelled Aquariids, tend to be faint, and the Alpha Capricornids rarely create more than five meteors an hour.

Active from July 17 to Aug. 23. Peak night: Aug. 12 to 13.

A favorite among skywatchers, the Perseids are one of the strongest showers each year, with as many as 100 long, colorful streaks an hour.

It is a show best viewed from the Northern Hemisphere. This year, observers may have to contend with light from the moon, which will be nearly 84 percent full on the night the Perseids peak.

Earth’s shadow will cross over the moon, creating the effect that some call a blood moon. The eclipse will be most visible in Asia and parts of Australia, but also experienced in Africa and Europe.

The autumnal equinox is one of two points in Earth’s orbit where the sun creates equal periods of daytime and nighttime across the globe. Many mark it as the first day of the fall. Learn five facts about the autumnal equinox here.

Active from Oct. 2 to Nov. 12. Peak night: Oct. 22 to 23.

The Orionids are well loved by meteor shower aficionados because of the bright, speedy streaks they make near the group of stars known as Orion’s Belt. Like the Eta Aquarids meteor shower, which peaked in early May, the Orionids result when Earth passes through debris from Halley’s comet.

This shower can be seen from both hemispheres. Viewing conditions may be excellent this year because the moon will be only about 2 percent full.

Active from Nov. 3 to Dec. 2. Peak night: Nov. 16 to 17.

The Leonids produce some of the fastest meteors each year, at 44 miles per second, with bright, long tails.

Meteors from the Leonids can be spotted in the constellation Leo, and will be visible from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. This year, the moon will be 9 percent full, which is good news for those trying to spot the Leonids.

Active from Dec. 1 to Dec. 21. Peak night: Dec. 12 to 13.

Caused by debris from an asteroid, the Geminids are one of the strongest and most popular meteor showers each year. This shower is best viewed from the Northern Hemisphere, but observers south of the Equator can also witness the show.

The Geminids peak when the moon is nearly 40 percent full.

It’s the scientific start to winter in the Northern Hemisphere, when this half of the world tilts away from the sun. Read more about the solstice.

Active from Dec. 16 to Dec. 26. Peak night: Dec. 21 to 22.

A winter solstice light show, meteors from the Ursids appear near the Little Dipper, which is part of the constellation Ursa Minor.

Only skywatchers in the Northern Hemisphere will have a chance of seeing this shower. The moon will be 3 percent full.

Our universe might be chock-full of cosmic wonder, but you can observe only a fraction of astronomical phenomena with your naked eye. Meteor showers, natural fireworks that streak brightly across the night sky, are one of them.

Where meteor showers come from

There is a chance you might see a meteor on any given night, but you are most likely to catch one during a shower. Meteor showers are caused by Earth passing through the rubble trailing a comet or asteroid as it swings around the sun. This debris, which can be as small as a grain of sand, leaves behind a glowing stream of light as it burns up in Earth’s atmosphere.

Meteor showers occur around the same time every year and can last for days or weeks. But there is only a small window when each shower is at its peak, which happens when Earth reaches the densest part of the cosmic debris. The peak is the best time to look for a shower. From our point of view on Earth, the meteors will appear to come from the same point in the sky.

The Perseid meteor shower, for example, peaks in mid-August from the constellation Perseus. The Geminids, which occur every December, radiate from the constellation Gemini.

How to watch a meteor shower

Michelle Nichols, the director of public observing at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, recommends forgoing the use of telescopes or binoculars while watching a meteor shower.

“You just need your eyes and, ideally, a dark sky,” she said.

That’s because meteors can shoot across large swaths of the sky, so observing equipment can limit your field of view.

Some showers are strong enough to produce up to 100 streaks an hour, according to the American Meteor Society, though you probably won’t see that many.

“Almost everybody is under a light-polluted sky,” Ms. Nichols said. “You may think you’re under a dark sky, but in reality, even in a small town, you can have bright lights nearby.”

Planetariums, local astronomy clubs or even maps like this one can help you figure out where to get away from excessive light. The best conditions for catching a meteor shower are a clear sky with no moon or cloud cover, at sometime between midnight and sunrise. (Moonlight affects visibility in the same way light pollution does, washing out fainter sources of light in the sky.) Make sure to give your eyes at least 30 minutes to adjust to seeing in the dark.

Ms. Nichols also recommends wearing layers, even during the summer. “You’re going to be sitting there for quite a while, watching,” she said. “It’s going to get chilly, even in August.”

Bring a cup of cocoa or tea for even more warmth. Then sit back, scan the sky and enjoy the show.