SAN FRANCISCO: In the race for AI dominance, American tech giants have the money and the chips, but their ambitions have hit a new obstacle: electric power.

“The biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it’s the power and…the ability to get the builds done fast enough close to power,” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella acknowledged on a recent podcast with OpenAI chief Sam Altman.

“So if you can’t do that, you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can’t plug in,” Nadella added.

Echoing the 1990s dotcom frenzy to build internet infrastructure, today’s tech giants are spending unprecedented sums to construct the silicon backbone of the revolution in artificial intelligence.

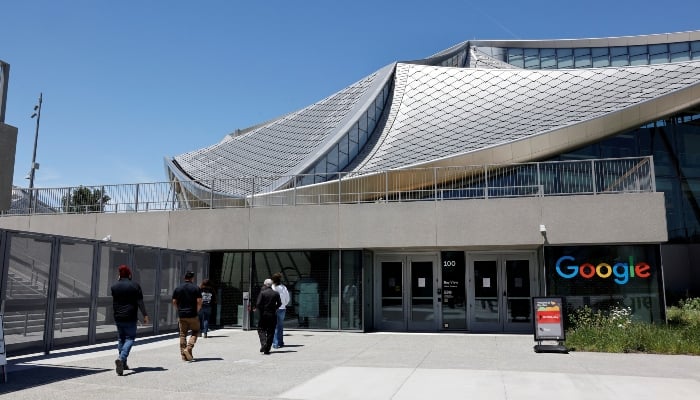

Google, Microsoft, AWS (Amazon), and Meta (Facebook) are drawing on their massive cash reserves to spend roughly $400 billion in 2025 and even more in 2026 — backed for now by enthusiastic investors.

All this cash has helped alleviate one initial bottleneck: acquiring the millions of chips needed for the computing power race, and the tech giants are accelerating their in-house processor production as they seek to chase global leader Nvidia.

These will go into the racks that fill the massive data centres — which also consume enormous amounts of water for cooling.

Building the massive information warehouses takes an average of two years in the United States; bringing new high-voltage power lines into service takes five to 10 years.

Energy wall

The “hyperscalers,” as major tech companies are called in Silicon Valley, saw the energy wall coming.

A year ago, Virginia’s main utility provider, Dominion Energy, already had a data-centre order book of 40 gigawatts — equivalent to the output of 40 nuclear reactors.

The capacity it must deploy in Virginia, the world’s largest cloud computing hub, has since risen to 47 gigawatts, the company announced recently.

Already blamed for inflating household electricity bills, data centres in the United States could account for 7% to 12% of national consumption by 2030, up from 4% today, according to various studies.

But some experts say the projections could be overblown.

“Both the utilities and the tech companies have an incentive to embrace the rapid growth forecast for electricity use,” Jonathan Koomey, a renowned expert from UC Berkeley, warned in September.

As with the late 1990s internet bubble, “many data centres that are talked about and proposed and in some cases even announced will never get built.”

Emergency coal

If the projected growth does materialise, it could create a 45-gigawatt shortage by 2028 — equivalent to the consumption of 33 million American households, according to Morgan Stanley.

Several US utilities have already delayed the closure of coal plants, despite coal being the most climate-polluting energy source.

And natural gas, which powers 40% of data centres worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency, is experiencing renewed favour because it can be deployed quickly.

In the US state of Georgia, where data centres are multiplying, one utility has requested authorisation to install 10 gigawatts of gas-powered generators.

Some providers, as well as Elon Musk’s startup xAI, have rushed to purchase used turbines from abroad to build capability quickly. Even recycling aircraft turbines, an old niche solution, is gaining traction.

“The real existential threat right now is not a degree of climate change. It’s the fact that we could lose the AI arms race if we don’t have enough power,” Interior Secretary Doug Burgum argued in October.

Nuclear, solar, and space?

Tech giants are quietly downplaying their climate commitments. Google, for example, promised net-zero carbon emissions by 2030 but removed that pledge from its website in June.

Instead, companies are promoting long-term projects.

Amazon is championing a nuclear revival through Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), an as-yet experimental technology that would be easier to build than conventional reactors.

Google plans to restart a reactor in Iowa in 2029. And the Trump administration announced in late October an $80 billion investment to begin construction on ten conventional reactors by 2030.

Hyperscalers are also investing heavily in solar power and battery storage, particularly in California and Texas.

The Texas grid operator plans to add approximately 100 gigawatts of capacity by 2030 from these technologies alone.

Finally, both Elon Musk, through his Starlink program, and Google have proposed putting chips in orbit in space, powered by solar energy. Google plans to conduct tests in 2027.